You know when you carve out a Halloween pumpkin with that special spoon that has the rough edges? That’s how I feel inside right now. Utterly and completely carved out. My heart feels jagged, wounded, not smooth. Cracked into a million pieces. Gutted. Weary.

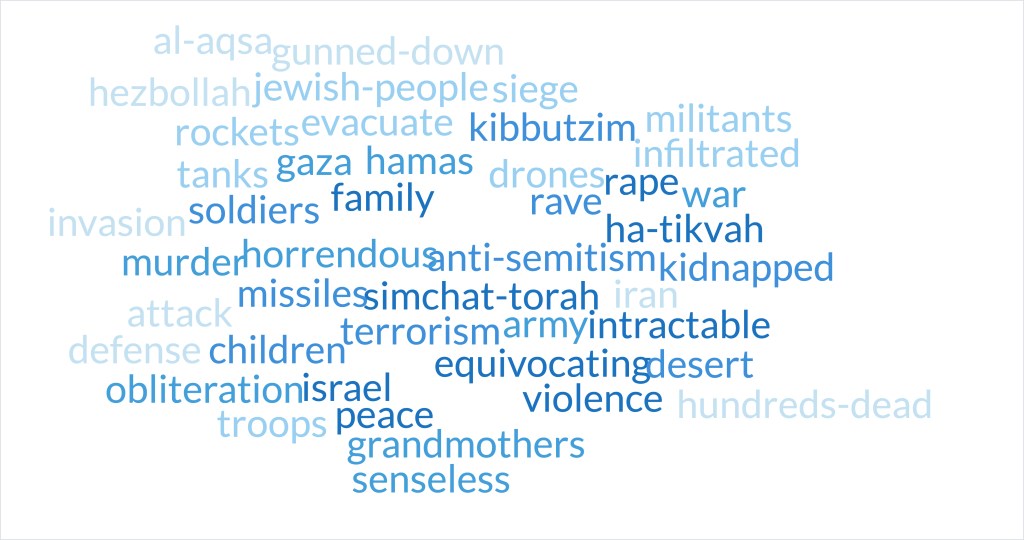

On October 9th, I made my first word cloud of the words that had been swimming around in my head since October 7th. Making word clouds felt like the most concrete thing I felt capable of doing with my thoughts, my feelings, with the headlines I was reading and what they brought up inside me. Some were entirely of sentences from the headlines. Others were things I had thought or said to or heard from people in my life. I made one word cloud with the names and ages of all of the hostages, taking the time to look at each of their photos, to look into their eyes. One word cloud focused on the suffering of the children, both Israeli and Palestinian children. God, that one hurt. All I could do was feel. And make word clouds. Sometimes only feel.

It’s day 55 since October 7th and this is the first time I have been able to sit down and really write. This is scary to share. I feel vulnerable and frayed. But I can’t keep it inside anymore.

~~~~~~~

While I certainly didn’t start from zero, I have spent a lot of the past 55 days learning – filling in the gaps in my knowledge and understanding of the history of Israel, the history of the conflict between Jews and Palestinians, between Jews and Arabs, between Israel and the countries and people all around her. I have done what I can to understand the history and cultures and politics to try and make sense of what happened on October 7th and since. For me, it feels like a critical obligation, as a Jew and as a human, to understand and to stay connected.

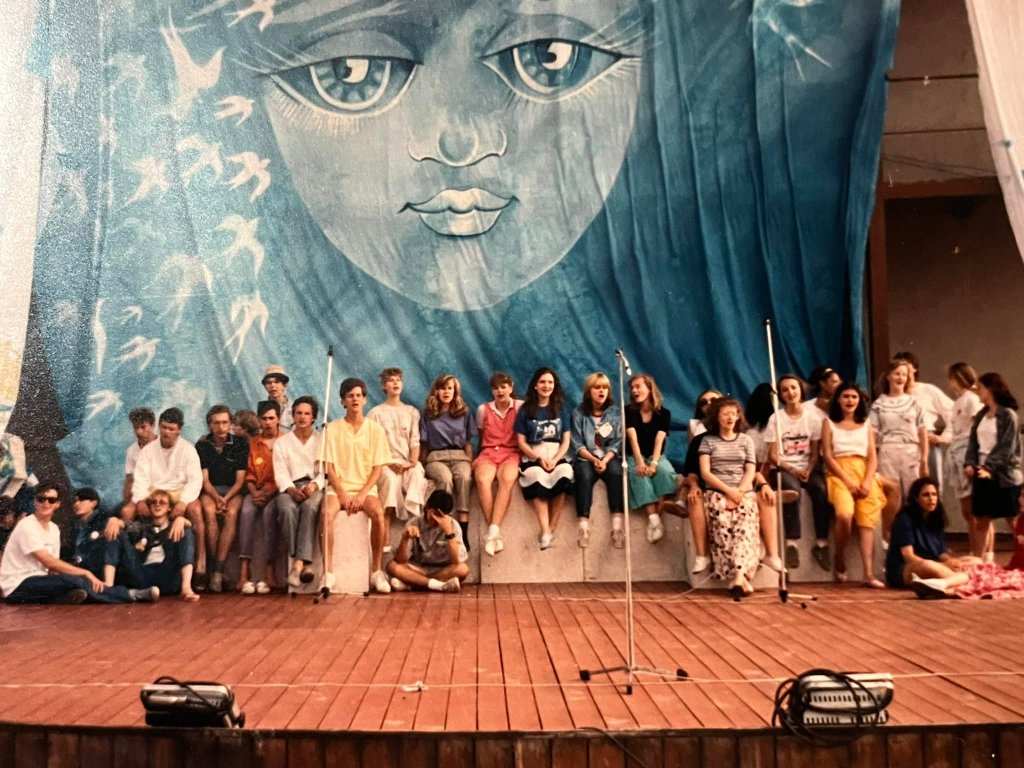

I have really missed my father especially these past 55 days. He was the one who gave me my love for history because it was also his own love. He taught me about the long arc of history and the big picture, about nuance and the grey areas, about geopolitics, about migration and integration and being an insider and an outsider at the same time. He told me our family’s story as refugees from so many parts of the world over so many centuries since their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula. He had a way of helping to make sense of the most confusing stories – when I was in elementary school and had to write an essay about a current event and I chose the Iran Hostage Crisis, when I was in high school and had just come back from a peace mission to the Soviet Union during the final years of the Cold War, or when I was in college trying to understand the U.S.’s role in eliminating leftist movements in Latin America. My father would add his personal experience as a citizen of the world who had lived in six countries, including Israel, and who spoke as many languages, including both Hebrew and Arabic. And he would throw in just the right amount of sentimentality, wistfulness and nostalgia, the kind you feel when you’re reading historical fiction or watching a movie about a family’s saga through time and place.

~~~~~~~

I can’t take my eyes off of the videos and photos of the hostages that have been released by Hamas and returned to Israel in the past week. The little boy named Gal who shares my name. The little girl named Alma who reminds me of photos I have of myself when I was young. The Thai and Philippino nationals leaving the hospital accompanied by song as they head to the airport to return home. Yaffa, the 85-year-old Holocaust survivor. The 13-year-old girl named Gali running with relief to hug her mother, their bodies absorbed one with the other. The brother and sister, Maya and Itay, who had both been held hostage but who were released at different times, reunited in the hospital. Mia sobbing in her mother’s arms after Mia’s release today, day 55. 4-year-old Avigail, reunited with her aunt and uncle and grandparents, the people who will raise her because her parents were murdered by Hamas on October 7th.

How can I see these without becoming every single one of them? I feel like I am every single child. Every single mother. Every single sister. Every single aunt.

How do these children, these families move forward from this trauma? How does a country? A people?

~~~~~~~

The city of Oakland, California, where I used to live, held a city council meeting a few days ago to decide on making a statement about the war between Israel and Hamas, as a city that “loves life.” I don’t know how many people spoke at the four-hour meeting, but I heard some of those who chose to make statements against Israel, against Jews. Those statements were disgusting, ignorant, hateful, false, lies, and/or completely absurd. The 1200+ people massacred by Hamas on October 7th were actually killed by the IDF?? Seriously? I don’t have a TikTok account and I’ve been out of college for 30 years so I don’t know if either of those spaces are where they got their information, but I shudder for the fate of humanity if this is the kind of garbage people believe so deeply that they choose to scream about it at a city council meeting. And don’t get me started on the “this is simply armed resistance by the Palestinian people” narrative. If that’s how you justify or dismiss the monstrous slaughter and kidnapping of innocent people for the sole reason that they are Jewish, then your heart is a cold, cold place and I have nothing to say to you.

~~~~~~~

A few weeks after October 7th, someone I didn’t know personally but whom I had followed on Instagram posted some social media memes essentially saying the same thing, images and words of parachuting terrorists representing armed resistance fighting white capitalism and settler colonialism, all of those simplistic, unnuanced, and antisemitic tropes that are everywhere right now. I wrote her a DM, asking her not to forget the massacre of Jews, not to ignore our generational traumas that also matter, not to completely dismiss an entire people as she supports another. She wrote me back, and her response took me time to process because it was the most vile, hateful, nasty, angry message I have ever received from anyone ever. She made all kinds of assumptions about me, about my whiteness, about my family, about Jews, about my views, about what I care about. To her, I was not a person with feelings, I was a representation of something she felt superior to, and the language she used was arrogant and abusive. I took the time to reply to her reply, thoughtfully and with vulnerability, even though what I wanted to write to her was a lot more angry and mean and filled with profanity. Afterwards, I tried to make one of those elimination poems from her words, where you black out most of the words from a paragraph and leave a few remaining words that form a poem that completely changes the energy of the original message – but I couldn’t do it. There weren’t enough gentle or even neutral words in her message to turn her hatred into love and compassion.

~~~~~~~

Since October 7th, I have unfollowed almost every Instagram account of people I had previously admired and learned from. Progressive thinkers who had resonated with the values of social justice I have stood for and worked for since my teens. Leaders in social justice spaces, racial justice spaces, gender and LGBTQ+ and reproductive justice spaces. They, like this woman I had written to, repeatedly dismissed the massacre of Jews, completely ignored any nuance or understanding of the complexity of this conflict, justified the murder and kidnapping of Jews as Palestinian resistance, threw out messages such as “Israel is responsible for what happened to them on October 7th,” thoroughly dismissed (my) Jewish existence, and shared memes as a form of their protest against Israel’s right to exist and defend her people.

My Instagram now consists of Israelis and other Jews, cute animals, a GenEx mom who makes parodies about being a GenEx mom, and potters who make ceramics that inspire my own.

“Who are my heroes now?” I asked one of my oldest friends on the phone last night. Who are my heroes now? And how do I resist the urge to go tribal and close myself off to connection with anyone outside my tribe? I am an empath and a connector, and this is not an easy time for either.

It is an incredibly tiring time to be a Jewish person. To have to defend your right to exist in the face of this kind of hatred, this kind of madness. Israel is brutally attacked, and within 48 hours, antisemitism surfaces from its never so hidden place and communities around the world turn against the Jewish people. “The world,” I said to my husband some weeks ago, “is completely upside-down.”

~~~~~~~

The last time I was in Israel was in February of 2008. I left with my family just before Valentine’s Day, 4 months earlier than we were supposed to return home. I was pregnant with my second daughter, and we had found out a few weeks before that she had a life-threatening birth defect that would require intense care and the support of our family and friends. I was scared of what was ahead, but I was relieved to be leaving Jerusalem.

The 7 months we spent there had been hard on me. I spent 6 weeks of them in excruciating pain with shingles, and recovered just before we found out about our daughter’s condition at her ultrasound. We lived across the street from a massive construction site, and the sound of impact hammers was constant and wore through every last nerve in my body. I struggled to find my footing and purpose in the city of my birth. Where my husband was finally finding his purpose as he began rabbinical school. Where my older daughter was beginning to learn Hebrew in the most organic way at her Israeli preschool. I remember when our plane took off from Ben Gurion Airport, and I exhaled with relief in spite of the unknowns ahead.

Since February of 2008, I have often said to myself and others, “I have a complicated relationship with Israel, even though it is where I was born.” I got tired during those 7 months there of arguing with the aggressive vendors at the market who wouldn’t accept that I had brought my reusable bags and would force plastic bags on me every single time I went to buy hummus or vegetables. Why does everyone here have to be so intense and high strung? Maybe I am just way too sensitive for this place, I remember thinking time and time again. It pained me to see the separation wall between Jerusalem and the West Bank in the distance from the main street near our apartment. I cried at a Jewish Film Festival screening several years later at the end of a film about the Religious Zionist settler movement that has for years contributed to preventing a two-state solution between Israel and the Palestinian people. I have struggled along with so many Israelis who spent the 11 months before October 7th protesting against Netanyahu’s right-wing government, afraid of what Israel would look like in the future under this government in the same way I fear what the U.S. will look like if trump becomes president again.

I was born in Jerusalem. I was a toddler in Israel during the Yom Kippur War. I have a lot of family and friends who are Israeli, some of whom are fighting in Gaza right now, all of whom are so deeply impacted by October 7th and the weeks since. When I visited Israel with my father when I was 9 years old for my cousin’s wedding, I remarked to him in awe, “Everybody here looks like me!” I saw myself in their faces, in their thick unruly hair. I spent 6 weeks in Israel when I was traveling in the mid-1990s. I turned 23 there. I spent time with all of my family, with my parents’ oldest friends, people who had known me as a baby. I learned about our history, my history. I traveled all the way to the north where you can see the Golan Heights, and all the way to the south, through the Negev desert, to the beaches of Eilat. I visited Chagal’s stained glass windows of the Twelve Tribes of Israel in the chapel of the hospital where I was born. I found a painting at Yad Vashem signed by an artist who shared my grandfather’s last name, a Holocaust survivor who turned out to be a distant relative by marriage. At Yad Vashem I added the name of my mother’s half brother, a child who was murdered by the Nazis, to the hall where children’s names are recited through speakers as you see their names and faces on the walls.

~~~~~~~

I am married to a public Jewish person. My husband is a rabbi, and since October 7th, he has been living and sleeping and breathing Israel, the horrific events of that day, speaking out against antisemitism in our community, holding his congregation while also carrying his own pain and generational trauma. As I write this, he is in Israel, a witness to her people’s pain and grief, their resilience and fortitude, their solidarity and coming together. His grandparents were also Holocaust survivors, our families came from the same corner of Poland. Since October 7th I have been holding him, and I have been holding my own pain and generational trauma, the pain and trauma of my Jewish family and friends all over the world, and the pain and trauma of Israel and her people.

That’s how it is when you are Jewish – none of this is separate from any of us, we are all connected. When you ask if I have people there, how do I explain that we all have people there?

~~~~~~~

I am the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors on one side and of Sephardi Mizrachi refugees on the other. My husband once told me, years before we were married, that I couldn’t not be Jewish even if I tried. He’s right. My Jewishness is in my core. It has always been in the water of my upbringing, of my sense of who I am. It’s in the food I grew up eating, in Shabbat candles lit when my mom felt like making roast chicken and rosemary potatoes in butter on a Friday night, in the transliteration of the words to Maotzur that was on the back of the box of Hanukkah candles we would get for free every year from Chabad, in the Egyptian haroset my father would make from his grandmother’s handwritten recipe. Of course I found community with other Jewish students when I began college. Where else would I find my people, my tribe, my easy and generous welcome?

My relationship with Israel is no longer complicated. In the days since October 7th, I realize that it is indelible. Israel is a part of me, even as I wrestle with feelings that aren’t simple, that exist in the grey areas. Israel is where I come from. It is where my people are. It is where I could return if I wanted, if it became more dangerous for me here than there. It is where I so easily could have grown up and lived my life, had my parents not made the decision to move when I was little.

I often wonder what I look like, how I behave, who I am in a parallel reality where I have never been anything other than Israeli… Would I be hardened and intense like the Israelis in the market in Jerusalem; less hypersensitive maybe? Would I be mighty and strong, a badass, having completed my military service? What kind of work would I do? Would I have taken my empathic self and become a trauma psychologist or a social worker? Who would my partner be, my children? Where in Israel would I live? How would I feel when my children went to fight?

Who would I be, having grown up with this reality of constant threat in my day-to-day, for my entire life? Would I even notice if I didn’t know anything different, or would it just be as much in the water as my Jewishness?

What would I believe – about the world, about people, about life – as an Israeli in Israel? What would have changed for Israeli Gal, in that parallel reality, on October 8th?

![tikva's quilt 6 09 005[1].JPG](https://lovebeautyabundance.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/tikvas-quilt-6-09-0051.jpg)

![tikva's quilt 6 09 021[1]](https://lovebeautyabundance.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/tikvas-quilt-6-09-0211.jpg)